I recently spoke with Marinel de Jesus, a solutions journalist who’s working to create a more equitable travel industry through both her trekking company, Global Equity Treks, and nonprofit, The Porter Voice Collective.

Interview with Marinel de Jesus, Equity Global Treks and The Porter Voice Collective

As a fellow solo female traveler, I’ve followed Brown Gal Trekker on Facebook for years now. After we both participated in a webinar on sustainable tourism this summer, I asked Marinel, the one-woman force behind the adventure travel media company, if I could learn more about her quest to create a more equitable travel industry. Luckily for me, she agreed to an interview, and we had a fascinating hour+ conversation. She’s currently back in Peru, her home base, after being stranded for 294 days (!) in Mongolia following the March 2020 border closures.

Photo credit: Marinel de Jesus

Who is Marinel de Jesus?

Marinel, a first-generation immigrant from the Philippines, is a former civil rights attorney who practiced law for 15 years before leaving it all behind in 2017 to become a digital nomad.

As Marinel rose through the ranks of her demanding legal career in Washington, D.C., she discovered she had a passion for mountain trekking and started organizing trips through Meetup.com to share her love for trekking with others. From 2014 to 2015, she got a taste of nomadic life, taking a one-year sabbatical to travel solo to 21 countries. Promptly upon returning, she sold her three-bedroom house and most of her belongings, and moved into a small apartment.

I started the process of being a minimalist…Being away for a year made me realize my backpack was the only thing I wanted.

In 2016 she launched a social enterprise tour company, Peak Explorations, which this year became part of Brown Gal Trekker. Now known as “Equity Global Treks,” it offers transformational journeys, with the ultimate goal of achieving workforce equity in the trekking tourism industry by uplifting women and indigenous communities. Then in 2019, Marinel founded the The Porter Voice Collective (PVC), a nonprofit organization that seeks to amplify the voices and advance the rights of porters who work in the mountains of Nepal, Peru and Tanzania.

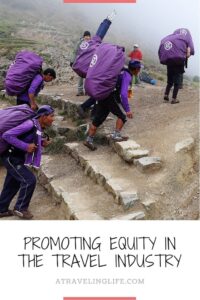

Porters supporting a G Adventures trek in Peru (Photo credit: Marinel de Jesus)

How did you make the transition from lawyer to travel company founder, advocate and journalist?

In May 2017 my mother passed away suddenly, and basically that was it. That was the shift. The last day I was a lawyer was the day she died. After the funeral, it was clear I wasn’t going back. There was no fear anymore. It was the gift she gave me.

I didn’t regret anything. I never did.

I think before my mom’s death I always had fear, like everyone else. You don’t want to change your lifestyle. You don’t want to give up your career. It’s scary.

How did you get involved in porter issues?

When I organize trips, I really get to know the locals. Maybe I’m nosy. Over a decade I learned about the issues, I’d have people confide in me like they wouldn’t with a journalist or a tourist. Maybe because I look like them.

I already knew there were some problems, but when I went full time with Peak Explorations, I started digging into it. The treatment of them is so mediocre—they’re underpaid or sometimes not even paid. They don’t have insurance. They don’t have a safety net. So in 2019, I decided to start a nonprofit organization to expose the issues.

A lot of tourists are still in denial.

I want to make tourists become advocates and be the ones that create change. PVC is the outlet for me to do that, and use all forms of media to educate for human rights for the porters in Nepal, Peru and Tanzania.

What have you accomplished so far?

When I launched PVC, I already had a project in mind. I was in Peru and talking a lot with the porters. At first I was just going to go to where they hang out after trips and have conversations with them.

There were a lot of complications, though, like the language barrier—they speak Quechua. They don’t even speak Spanish. And there are a lot of trust issues. If you’re an outsider—even from Lima—they don’t trust you because they’ve been so marginalized and oppressed.

I realized the issue was so deep that the best way to advocate was to create a documentary. “KM 82″ was the film we launched in 2019 to investigate the issues on the Inca Trail. I created a production team, and we talked to Alberto Huaman Huamanhuillca, president of Federacion de Porteadores del Camino Inka (Federation of Porters of the Inca Trail), and attended some of their meetings. He wanted to speak up despite all the risks, and I wanted to give him a platform for him to tell his truth.

If someone doesn’t like what you’re doing, you really should do it.

We finished the film in February 2020*, and by that time we were getting threatened by tour operators. There were a lot of people opposing our project because it was telling the truth. A few days before I left for Mongolia, I got a death threat.

*Note: Post-production editing of the documentary was postponed due to the pandemic.

Travelers with Equity Global Treks agree to follow six principles: 1. Respect for all 2. Anti-oppression/colonial mentality/imperialism 3. Anti-racism/sexism/harassment 4. Anti-white savior mentality 5. Aim to decolonize the tourism industry and destinations 6. Practice land acknowledgements (Image credit: browngaltrekker.com)

How did Peak Explorations transform into Equity Global Treks?

During COVID I went through a self-reflection phase like everyone else. I asked, “What’s the purpose of Peak Explorations?” In the beginning it was just to travel and take people places, and go hiking.

I realized I have a deeper mission than that, and the name didn’t feel aligned anymore with all the work I’m doing with the porters and women, so I said, “What the heck. Let’s just call it what it is.” What I really want is to create equity, so I wanted the mission to be more transparent.

How is what you do different?

In the beginning I marketed trips that are cookie cutter—Mount Kilimanjaro, Everest Base Camp. It was just hiking, nothing special. Now I’m more mindful of what I’m doing for every trip that I offer.

They (people in the tourism industry) always refer to CBT, or Community-Based Tourism. What does that mean? Who’s leading it? Who’s making the decisions? They (the community) are just being used to market a product. They’re being paid for the services they provide, but they have no say. I have a problem with that.

I call the projects I do “community-led.” This means the real leaders of the project are the locals, from the community—not an outside tour company, which is the common model.

Photo credit: Marinel de Jesus

How to you ensure more equitable trips?

I do a lot of research on the ground. I have to work with local folks to make sure they’re ethical and equitable, and in line with my vision. I say, ‘You’re going to need to be transparent, you’re going to pay the porters this much money, you’re going to give them three meals a day.’ We also schedule a day where we spend time with the porters in their homes. We need to humanize them and not look at them like servants. They’re your hosts, and you’re their guests.

I lay it out, “You’re not going to be served.”

The other thing is our trips are women focused. Women are some of the most marginalized in the tourist industry. When I go to conferences, I mostly see white men at the top, and some white women. I hardly ever see people like me, to be honest.

What are some of the unique challenges facing women in tourism?

There are no safety protocols for mountain guides and porters—especially women. Gender discrimination and sexual harassment are real concerns for women in the industry. In Peru, women porters have confided in me that they are being harassed, but there are no consequences. There’s no way to report it, there’s no accountability. Through PVC we want to create a universal declaration to protect women and preserve their rights.

If we want to talk about sustainability and equity, we need to change the system to make it more welcoming and create safeguards for the rights of women.

The human rights aspect of the tourism industry is just such an uncomfortable topic that people don’t want to give it the day and time it deserves. No one wants to acknowledge it.

tourists at Machu Picchu

What’s your message to tourists?

I wish tourists would be more curious and ask questions. We have to learn what it means to be privileged. It’s all about being humble and admitting that we don’t know the whole story. Who’s been telling the story all this time? The people with power in the industry, and not the local people.

Tourists have a very strong voice because they’re funding this industry—where the money lies is where the power lies too.

Tourists are the culprits when it comes to being entitled, and perpetuating colonialism and white saviorism—things making the industry so inequitable. We all need to do our part. Education needs to come from all sides.

On September 13th, Khusvegi English & Nomadic Culture Camp was named the winner of the Launch Track at the Social Entrepreneurship Competition in Tourism 2021 hosted by the United Nations World Tourism Organization, TUI Care Foundation, Travel Massive, ITB Berlin, SINA, and Eberswalde University. Congratulations! Learn more about the competition and finalists.

What’s next?

I planning a big project in Mongolia now—it’s a 30-day nomadic culture camp (Khusvegi English & Nomadic Culture Camp). Every summer we’re going to host it with the eagle hunters. It’s promoting slow travel, and cultural immersion, so there’s more benefit to the community.

We have to give the mic and the platform to local people to hear what they have to say.

It’s really a community-led trip, and I’m facilitating it to connect them with the outside world. We want to cater to how they want to design it—they really want to host visitors in their homes. We’re going to set up yurt camps, so everyone is going to go eagle hunting for the weekend.

My hope is that when things get a bit better for each country, I’m going to start booking tours again. The only thing I have open now is Mount Kilimanjaro because Tanzania hasn’t had many closures.